Introduction

A persistent financial crisis, the rising of regional tensions, the concerns of a trade war and many other facts have recently been catching up with the M&A-friendly international environment. Protectionism seems now to pervade the new world order. Rising economic nationalism is threatening to impact M&A activity across all over the world, as governments and regulators take a suspicious look at “foreign” investments on nationally important companies in the name of free competition, fair trading and, most importantly, national security.

Government Intervention

Before we delve into the specifics of how government intervention may interfere with cross-border M&A transactions, it is of central importance to contextualize the geopolitical orientation which we are currently facing.

In general, it is important to notice how in the last decade the world has gone from the widely accepted (and welcomed) event of Globalization to a much more Macro-Regional Approach, in which we do not anymore have true globalization, but rather a concentration into larger trade blocks (like the E.U., the Asia-Pacific Region, the North American Region, ect.). Moreover, as of recently, following radical political changes like the advent of Brexit or even the election of Donald Trump, we are increasingly nearing stronger forms of nationalization. Globalization has indeed become synonymous to excessive liberalism and in direct response, conservative parties have really had a large upturn in the most recent elections worldwide. Furthermore, while the political divide between left and right-wing parties was previously much more moderated and narrow, we are nowadays witnessing a significantly wider political spectrum in which common grounds are much smaller and compromises are increasingly harder to share.

To evaluate how M&A transactions may be affected by the Government, we need to realize that there are both direct and indirect impacts of Government policy on M&A transactions. Moreover, while the direct impacts are observable, the indirect impacts are much less evident but just as significant. More specifically, while we are able to quantitatively graph the number of failed M&A transactions because of Government intervention, we are incapable of measuring how many otherwise viable M&A transactions are simply not even taken into consideration because some industries may be heavily oversighted by the government or be of importance to national policy.

One could also go as far as to argue that the very indirect effects of national policy on M&A transactions are by far the most severe, as many buyers completely exclude certain targets due to the fact that they may be of national interest to their respective governments and hence be impossible (or very hard/expensive) to acquire. Furthermore, while in previous times sensible industries were much more defined, like the Aerospace and Defence Industries (Aerospace and Defence companies have always been near to untouchable in the U.S.), nowadays, such boundaries seem to have been significantly blurred, with Utilities, Telecoms and Technology companies now becoming nationally sensitive. In short, the range of Industries which are of Government concern has significantly increased, as such companies increasingly carry sensitive information and comprise the backbone of a country.

Competition

Even though competition concerns are not a new matter, compliance with competition law requirements – and the related competition authorities’ power to veto in advance transactions – remains one of the most important way in which governments influence the M&A market. Thereby a competition authority considers that a merger transaction will have a detrimental impact on competition, it can require the merging parties to enter into commitments to divest in order to remedy those anti-competitive effects or even prohibit the transaction entirely.

In the United States, antitrust measures under the Trump administration are perceived as less substantial than in Europe. The US recently moved away from behavioural remedies (e.g. obligation to license key pieces of technology or enable access to infrastructure and key assets) used during Obama’s office. Instead, the current American Department of Justice has chosen to only impose structural remedies in respect to problematic M&A and the respective divestment of assets processes that may follow along.

In contrast, the EU has been more aggressive in enforcing antitrust measures for M&A. There are heavy sanctions for those providing misleading information even when this information is not of crucial nature. Furthermore, there have been concerns and damage claims related to innovation and competition theories of harm.

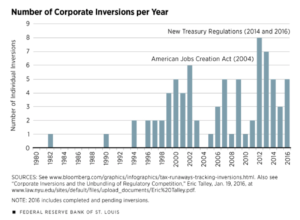

Tax Inversion

As provided for by the US Treasury, “a corporate inversion occurs when a U.S.-based multinational corporation restructures itself so that the U.S. parent is replaced by a foreign parent and the original U.S. company becomes a subsidiary of the foreign parent”.

Inversions are among the strategies set by US corporations to reduce taxes. The question of the tax residence of a company – the matter of the territoriality in which it produces its revenues and earnings – has gained momentum over recent years. While this practice has been for long used to save in tax expenses by relocating the residence of the parent company, in the US this practice is focused mainly on takeovers in order to transfer the company’s residence in countries where the corporate tax rate is not as high as the US one. The tax benefit can be substantial because the US corporate tax rate used to be the world’s most expensive (at least until the recent tax reform, which however is shown to have ambiguous effects on M&A activity).

Nevertheless, it is not just a US-based corporations practice. Over the years, tax inversion has been put in place by many companies throughout the world. For example, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, through its long restructuring process, decided to relocate its residence for tax purposes from Turin to Amsterdam. Even if not illegal, the practice has caught the attention of legislators when, between the 2013 and 2014, such “tax inversion deals” amounted to $100bn. The spark which set off the powder was the (failed) acquisition of AstraZeneca – a UK-based healthcare company – by Pfizer, the largest pharma corporation in the world. Since then, the US government initiated a path apt to transform the repatriated foreign-held capital into taxable dividends, subject to the US taxation.

National Interest

Even if the levels of protectionist sentiment and government intervention are growing, this has not been enough to create a major fall in M&A activity yet. Nevertheless, the governments’ involvement in deal dynamics has dramatically changed over time.

Globally, countries have started closely scrutinizing foreign acquisitions on the grounds of national interest. President Trump blocked a Chinese bid for Lattice Semiconductor Corp. due to national security concerns, while the UK parliament has recently proposed new legislation enabling the government to intervene more in M&A matters. The industries which are most affected by such intervention trend are all those industries which deal with sensitive data, advanced technology and defence, such as the healthcare and hi-tech ones.

Effects on M&A deals

In order to go into the details of the effects that such interferences have on M&A deals, we will focus on the US market – not only because it is the largest market in terms of M&A volume, but also because it serves as a general paradigm internationally.

We focus on three venues through which an M&A transaction may be blocked directly: firstly, it may be blocked by the Antitrust Authorities following concerns regarding competition and market functioning; secondly, certain transactions may be blocked following the passing of a certain bill which renders such transaction unlawful or unviable; lastly, and more generally, there may be direct Government Intervention my means of an executive order issued directly by the President (or similar circumstances) citing general motives along the lines of National Security or Policy.

As stated previously, indirect intervention and causes are much harder to grasp due to their much wider breadth and indeterminacy. A good example of indirect intervention interfering with M&A transactions is the entire “Trade-War” circumstance surrounding global trade at the moment. It is unclear what the consequences of trade-wars will have on future M&A trends, as we have not yet seen much in terms of tangible action on behalf of national authorities, but rather much more in terms of announced threats. To such extent, it is also worrying how such very aggressive policies are being used as political negotiating tactics, at the expense of certainty and investor sentiment. Notwithstanding its indirect effects, it is undoubtable how trade barriers will inevitably curb international M&A and decrease cross-border interest in large corporates.

The reality is that certainty is a predominant component that can very much influence the decision of managers to pursue an M&A transaction, as failed deals entail very large costs to the parties involved. While investment bankers will increasingly seek to lessen such uncertainty and get to common grounds, the reality is that such doubts tamper decision maker’s interest in M&A. It is also much unclear how to arrange for those who should cover expenses incurring from government scrutiny or intervention. Currently, pre-emptive measures seem to be the most viable option, with the interested parties deciding who will cover such costs before engaging into formal talks regarding a potential transaction. Still, more powerful counterparts sometimes obtain the so called “High Water Clause” which is very risky for a potential acquirer and declares that no matter what happens, the buyer will need to follow through with its payments and cover any damages/expenses incurring from unprecedented circumstances including government intervention.

Lastly, it is truly important to underline how governments meddling into M&A is not a partisan-based phenomenon but a matter of a more general political debate. As testified in the recent US presidential elections, M&A policy was a topic of central debate with Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump alike taking strong stances upon it. Today, withdrawn M&A is at record highs of $658bn – and has just as of recently surpassed pre-crisis levels.

While general sentiment would have us believe that republicans and right-wing parties are more fierce and restrictive in terms of M&A policy, the differences concern the industries involved rather than the broader policy decisions. The different parties hold different perspectives, but one is not necessarily more or less interventionist than the other. In fact, tax inversion transactions were a shared topic which warranted intervention, while drug pricing and regulation concerning pharmaceuticals was an example of a topic in which Trump was a lot less vocal and involved than his democrat counterparts (including both Clinton and Sanders).

Case Study 1 – UK Government Intervention and New Legislation

The UK government recently started to amend the Enterprise Act (2002) and thus adjust present-day policies which favour investment in UK firms. Under the Enterprise Act, governments can only intervene in “exceptional public interest” takeovers, which pose a threat to national security or the stability of the banking system. By altering the act, takeovers in the advanced technology and military sectors could be more effectively examined and potentially blocked. The government also recommends that the supplier turnover threshold should be reduced from £70m to £1m and that the requirement of mergers to increase the share of supply to over 25% is eliminated.

Over previous years, the UK government has also intervened in numerous mergers and acquisitions, with the general aim of maintaining economic stability and protecting local consumers and businesses. In 2006, Ferrovial acquired BBA in a transaction valued at £16bn. Due to the firm’s monopoly control over airports (60% market share in Britain and 84% in Scotland) and poor management of its operating facilities, Ferrovial was forced to sell three of its British airports. The commission chairman justified this decision by stating: “Bringing in new owners for some London and Scottish airports could lead to new routes being offered, pricing structures being reformed and more money being pumped in”. The acquisition of HBOS by Lloyds TSB at the height of the 2008 financial crisis illustrates another deal, where the UK government has taken action. During the time, the prime minister comforted the chairman of Lloyds TSB, by confirming that the government would relax competition rules if Lloyds TSB would purchase HBOS. However, 6,000 shareholders later filed a £550m court case, claiming that vital information about HBOS’ true financial health was withheld, such as £25bn of emergency support from the Bank of England and $18bn from the US Federal Reserve.

Case Study 2 – Protection against Foreign Investment

Chinese investments in the United States tripled in 2016 to approximately $46bn, thus motivating the Trump administration and also Angela Merkel to draft proposals whose aim is to make the sale of strategically important companies and know-how more difficult.

In Germany, for example, the new rules primarily concern software firms as well as businesses involved in the maintenance of critical infrastructure facilities and with large quantity access to cloud-stored data. Additionally, the German government’s review period for takeovers would be extended from 2 months to 4 months and information may even be collected from intelligence services to assess the true nature of the deal. The act is a response to the €4.5bn acquisition in May 2016 of the German robot manufacturer Kuka by the Chinese Midea Group.

A group of bipartisan lawmakers in Washington introduced legislation, supported by the Trump administration, aims to reduce both Chinese financial inflows and outbound investments conducted by US companies. Trump justifies this action by stating that increased protectionism will boost local employment, innovation and growth. It must also be considered that the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US currently possesses a limited scope and relies on voluntary filings from companies involved in mergers and acquisitions.

Broadcom’s intention to acquire Qualcomm in a transaction valued at $117bn may be regarded as the latest major deal highlighting the size and aggressiveness of Asian firms. Broadcom has in fact created a hostile takeover situation, by nominating 6 Broadcom candidates for Qualcomm’s board of directors. As Qualcomm is one of the biggest competitors to Chinese firms, the US government expressed several concerns about the structure of the semiconductor industry, as companies intensely compete to manufacture chips which permit 5G wireless technology and thus faster transmission of data. Given the difficult circumstances, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US asked Qualcomm to postpone its shareholder meeting by 30 days. Subsequently, President Trump blocked the transaction through an executive order, citing a “national security concern” as rationale for such decision.

Case Study 3 – Tax Inversion Phenomenon

In November 2015, Pfizer and Allergan, the two giants in the US pharmaceuticals industry, announced a $160bn merger in which Pfizer shareholders would have taken control of a 56% stake in the combined company, hence remaining under the 60% threshold that would have prevented any tax-related benefit coming from the relocation of the merged entity headquarters in Ireland, where Allergan is currently based.

However, the Obama administration at that time worked to review rules to make tax inversion harder to exploit. With the new rules, as a result of the transaction Pfizer’s shareholder would have controlled an 80% stake in the merged company, far above the above mentioned 60% threshold. Eventually, no tax inversion was exploitable by means of such deal and therefore the merger was withdrawn.

The real loser in this abandoned deal was Pfizer CEO, who for years had been looking for a partner to exploit the tax inversion scheme: examples include the attempted deal with AstraZeneca in 2014, Valeant in Canada or the UK-based GlaxoSmithKline.

0 Comments